Bonnard and the Nabis – The painting of rebellious Post-Impressionist artist

The text below is the excerpt of the book Bonnard and the Nabis (ASIN: 1646993179), written by Albert Kostenevitch, published by Parkstone International.

In October 1947, the Musée de l’Orangerie arranged a large posthumous exhibition of Bonnard’s work. Towards the close of the year, an article devoted to this exhibition appeared on the first page of the latest issue of the authoritative periodical Cahiers d’Art. The publisher, Christian Zervos, gave his short article the title “Pierre Bonnard, est-il un grand peintre?” (Is Pierre Bonnard a Great Artist?) In the opening paragraph Zervos remarked on the scope of the exhibition, since previously Bonnard’s work could be judged only from a small number of minor exhibitions. But, he went on, the exhibition had disappointed him: the achievements of this artist were not sufficient for a whole exhibition to be devoted to his work. “Let us not forget that the early years of Bonnard’s career were lit by the wonderful light of Impressionism. In some respects he was the last bearer of that aesthetic. But he was a weak bearer, devoid of great talent. That is hardly surprising. Weak- willed, and insufficiently original, he was unable to give a new impulse to Impressionism, to place a foundation of craftsmanship under its elements, or even to give Impressionism a new twist. Though he was convinced that in art one should not be guided by mere sensations like the Impressionists, he was unable to infuse spiritual values into painting. He knew that the aims of art were no longer those of recreating reality, but he found no strength to create it, as did other artists of his time who were lucky enough to rebel against Impressionism at once. In Bonnard’s works Impressionism becomes insipid and falls into decline.” It is unlikely that Zervos was guided by any personal animus. He merely acted as the mouth- piece of the avant-garde, with its logic asserting that all the history of modern art consisted of radical movements which succeeded one another, each creating new worlds less and less related to reality.

The history of modern art seen as a chronicle of avant-garde movements left little space for Bonnard and other artists of his kind. Bonnard himself never strove to attract attention and kept away altogether from the raging battles of his time. Besides, he usually did not stay in Paris for any length of time and rarely exhibited his work. Of course, not all avant-garde artists shared Zervos’s opinions. Picasso, for example, rated Bonnard’s art highly in contrast to his own admirer Zervos, who had published a complete catalogue of his paintings and drawings. When Matisse set eyes on that issue of Cahiers d’Art, he flew into a rage and wrote in the margin in a bold hand: “Yes! I maintain that Bonnard is a great artist for our time and, naturally, for posterity. Henri Matisse, Jan. 1948.” Matisse was right. By the middle of the century Bonnard’s art was already attracting young artists far more than was the case in, say, the 1920s or in the 1930s. Fame had dealt strangely with Bonnard. He managed to establish his reputation immediately. He never experienced poverty or rejection unlike the leading figures of new painting who were recognized only late in life or posthumously — the usual fate of avant-garde artists in the first half of the twentieth century. The common concept of peintre maudit (the accursed artist), a Bohemian pauper who is not recognized and who readily breaks established standards, does not apply to Bonnard. His paintings sold well. Quite early in his career he found admirers, both artists and collectors. However, they were not numerous. General recognition, much as he deserved it, did not come to him for a considerable time. Why was it that throughout his long life Bonnard failed to attract the public sufficiently? Reasons may be found in his nature and his way of life. Bonnard rarely appeared in public, even avoiding exhibitions. For example, when the Salon d’Automne expressed a desire in 1946 to arrange a large retrospective exhibition of his work, Bonnard responded to this idea in the following way: “A retrospective exhibition? Am I dead then?” Another reason lay in Bonnard’s art itself: not given to striking effects, it did not evoke an immediate response in the viewer. The subtleties of his work called for an enlightened audience. There is one further reason for the public’s cool attitude towards Bonnard. His life was very ordinary; there was nothing in it to attract general interest. In this respect, it could not be compared with the life of Van Gogh, Gauguin or Toulouse-Lautrec. Bonnard’s life was not the stuff legends are made of. And a nice legend is what is needed by the public, which easily creates idols of those to whom it was indifferent or even hostile only the day before. But time does its work. The attitude towards Bonnard’s art has changed noticeably in recent years. The large personal exhibitions which took place in 1984-85 in Paris, Washington, Zurich and Frankfurt-am-Main had considerable success and became important cultural events.

What was Pierre Bonnard’s life like? He spent his early youth at Fontenay-aux-Roses near Paris. His father was a department head at the War Ministry, and the family hoped that Pierre would follow in his father’s footsteps. His first impulse, born of his background, led him to the Law School, but it very soon began to wane. He started visiting the Académie Julian and later the Ecole des Beaux- Arts more often than the Law School. The cherished dream of every student of the Ecole was the Prix de Rome. Bonnard studied at the Ecole for about a year and left it when he failed to win the coveted prize. His Triumph of Mordecai, a picture on a set subject which he submitted for the competition, was not considered to be serious enough. Bonnard’s career as an artist began in the summer of 1888 with small landscapes painted in a manner which had little in common with the precepts of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. They were executed at Grand-Lemps in the Dauphiné. Bonnard’s friends — Sérusier, Denis, Roussel and Vuillard — thought highly of these works. Made in the environs of Grand-Lemps, the studies were simple and fresh in colour and betrayed a poetic view of nature reminiscent of Corot’s. Dissatisfied with the teaching at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and at the Académie Julian, Bonnard and Vuillard continued their education independently. They zealously visited museums. During the first ten years of their friendship, hardly a day went by when they did not see each other.

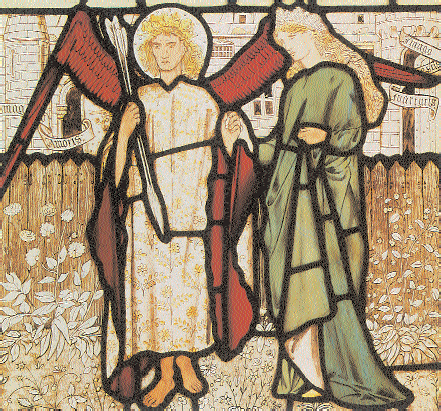

The Nabis group, assembled by Paul Sérusier, was comprised of several members from the Académie Julian. In refusing to comply with the rules of Impressionism, these artists claimed instead to be largely influenced by Gauguin. Their name, derived from the Hebrew Nahbi, signifies a prophet or a visionary, thus symbolizing their will to discover the sacred nature of writing. They were largely influenced by Japanese art, most notably wood engravings, as well as popular and primitive art and the art of the symbolic artist, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Although they all differed considerably from one another, there were two lines of thought in particular on which they all agreed; firstly, subjective misinterpretation, born within the artist’s emotions accentuating certain aspects of the subject that is being depicted, and secondly, objective misinterpretation ensuring the depiction finds its place in the fundamental order of the work. Their art is characterized by an absence of perspective and the use of pure tones and shades. They would all attempt to overcome the barrier between easel painting and decorative art, experimenting with illustration, wallpaper, stained-glass windows, tapestry, furnishings… The Nabis group united artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Félix Ker Xavier Roussel, Georges Lacombe, the sculptor Aristide Maillol and even Maurice Denis who claimed that, “before a painting is turned into a battle horse, a naked woman, or becomes any sort of trivial detail, it is essentially just a flat surface covered with colors that are assembled in a certain order.”And yet they addressed one another with the formal “vous”, while Bonnard addressed other members of the Nabi group with “tu”.

Bonnard’s intonations often have humorous overtones. Benois saw this as the source of the superficiality for which he reproached the artist. There might have been an element of truth in this, if Bonnard’s humour were present in all circumstances. But he used humour only when he wanted to avoid the direct expression of emotions. In a way, his special form of tact was akin to that of Chekhov. Though there was never any personal contact between these two men, they had much in common. Bonnard always added a touch of humour when he depicted children. The ploy reliably protected him against the excessive sentimentality often observed in this genre.

Bonnard had no children of his own. For many years he led a bachelor’s life. This seemed not to worry him in the least. If, however, one looks at his works as a kind of diary, a rather different picture emerges. In the 1890s-1900s he often depicted scenes of quiet domestic bliss. These scenes — the feeding of a baby, children bathing, playing or going for walks, a corner of a garden, a cosy interior — are both poignant and amusing. Of course, these aspects of life attracted the other Nabis, too, which was in keeping with the times. But in Bonnard’s work these motifs are not treated with stressed indifference, as in Vallotton’s. Bonnard does not conceal the fact that he finds them attractive. Yet it is not easy to discern a longing for family life in his work. One might suggest it but without much confidence. Bonnard seems to remind himself, as always with humour, that family life is undoubtedly emotionally pleasant, but there is much in it that is monotonous and even absurd — a truly Chekhovian attitude. The many commonplace situations treated on account of banality with a degree of humour are summed up in the monumental portrait of the Terrasse family, a work unprecedented in European art. Bonnard gave the picture the title The Terrasse Family (L’Après-midi bourgeoise). It was painted in 1900 and is now in the Bernheim-Jeune collection in Paris (another version is in the Stuttgart State Gallery). The title parodies Mallarmé’s eclogue L’Après-midi d’un faune. The artist had affection for his characters and not only because they were his relatives (Bonnard’s sister Andrée was married to the composer Claude Terrasse). Yet he depicted the dozen or so of them in an ironical parade of provincial idleness, in all its grandeur and its absurdity…

Explore Pierre Bonnard’s works here:

The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

To get a better insight into the Bonnard and the Nabis, continue this exciting adventure by clicking on Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon Australia, Amazon French, Amazon German, Amazon Mexico, Amazon Italy, Amazon Spain, Amazon Canada, Amazon Brazil, Amazon Japan, Amazon India, Parkstone International, Ebook Gallery, Kobo, Barnes & Noble, Google, Apple, Overdrive, Ellibs, Scribd, Bookbeat,

bol.com